Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome (HLHS)

~Introduction

Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome (HLHS) is a rare but extremely serious congenital heart defect in which the structures on the left side of the heart — including the left ventricle, mitral valve, aortic valve, ascending aorta and the aortic arch — are under‐developed or severely malformed. (CDC) Because the left side of the heart is the usual “high‐pressure” pump sending oxygenated blood into the systemic circulation (the body), when it is unable to do so the condition becomes life‐threatening very quickly after birth unless immediate intervention is undertaken. (Wikipedia)

In short: a baby with HLHS cannot rely on the standard left‐side pumping mechanism, and survival depends on early diagnosis, urgent medical and surgical management, and lifelong follow‐up.

In this article we will discuss the epidemiology, anatomy & development, causes, clinical presentation, diagnosis, treatment (including surgical staging), outcomes and long‐term considerations, and the psychosocial & future‐research aspects of HLHS.

~Epidemiology & Significance

HLHS is uncommon but carries significant clinical weight among congenital heart diseases. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), about 1 in every ~3,900 newborns in the U.S. are born with HLHS. (CDC) Other sources give slightly varied numbers (for example 1 in 4,300). (Indiana Government)

It accounts for approximately 2 %–3 % of all congenital heart defects. (Cleveland Clinic)

Importantly, despite its rarity, it contributes disproportionately to early infant mortality among cardiac‐defect cases: untreated, the prognosis is very poor. (PubMed)

Globally, advances in surgical and interventional cardiology have improved survival, meaning that more children with HLHS are surviving into childhood, adolescence and even adulthood. However, they remain in the “single‐ventricle” physiology category with lifetime risks. (Wikipedia)

~Anatomical & Developmental Basis

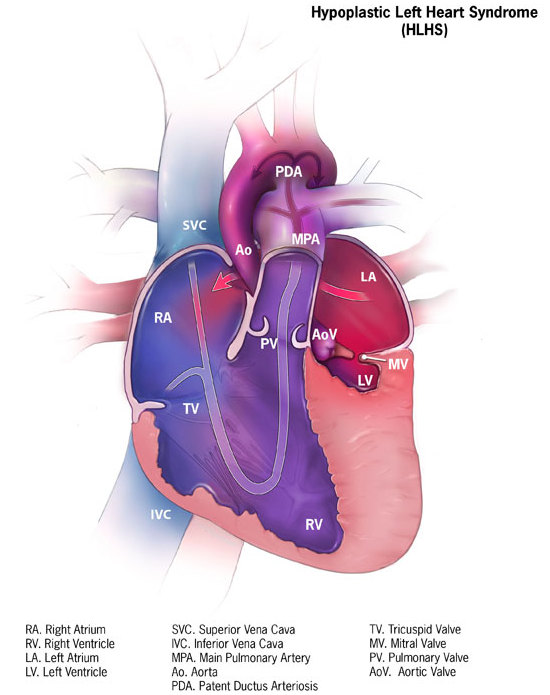

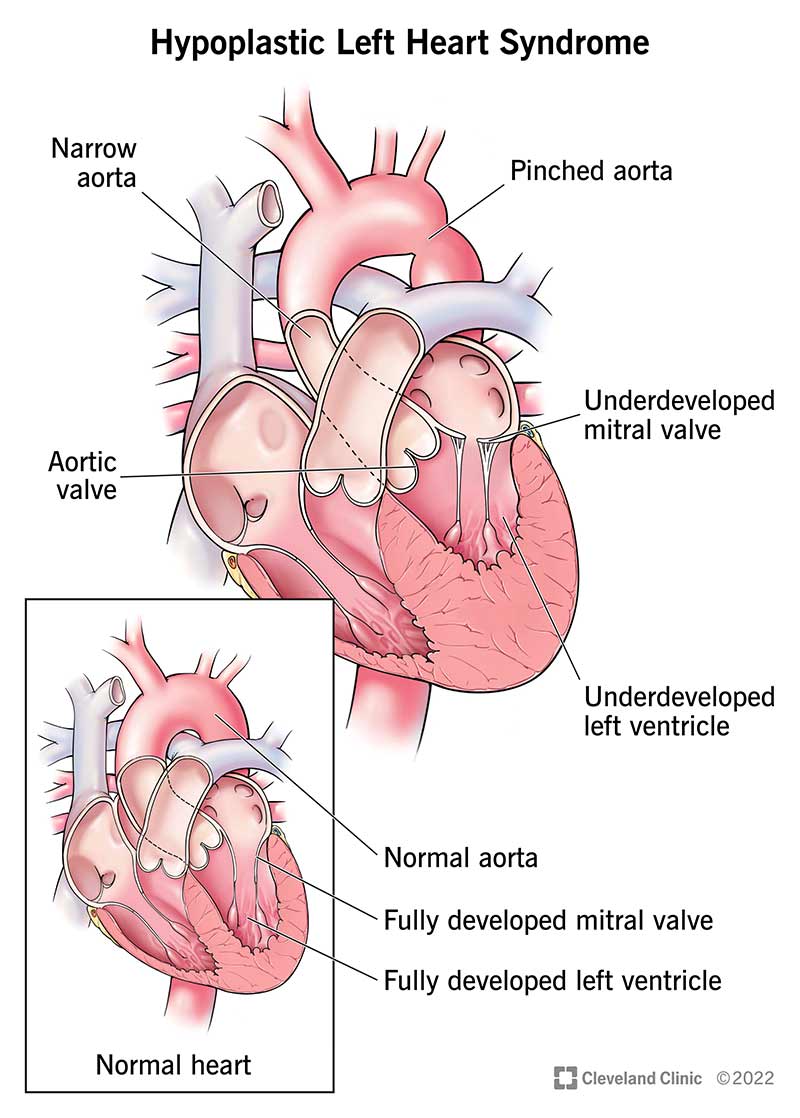

Normal vs Abnormal

In a normally developed heart, the left side (left atrium → left ventricle → aortic valve → aorta) receives oxygen‐rich blood from the lungs, pumps it at high pressure to supply the body, while the right side pumps deoxygenated blood to the lungs. In HLHS, many of the left‐side structures are small (hypoplastic) or non‐functional.

Structures typically affected in HLHS:

-

The left ventricle is under‐developed and too small to pump effectively. (CDC)

-

The mitral valve (between left atrium and left ventricle) may be stenotic or atretic (closed). (Wikipedia)

-

The aortic valve may be stenotic or atretic (closed or very narrow). (BioMed Central)

-

The ascending aorta and aortic arch may be hypoplastic (narrow) and unable to carry the systemic output adequately. (Mount Sinai Health System)

-

In many cases, an atrial septal defect (ASD) or patent foramen ovale remains so that the right side can mix some blood; likewise, the patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) is necessary early on. (Indiana Government)

Fetal & Neonatal Physiology

During fetal life, the baby’s circulation is different: the lungs are not yet used for oxygenation; the ductus arteriosus and foramen ovale allow shunting of blood. In HLHS, these fetal pathways are critically important to ensure that some blood reaches the systemic circulation despite the compromised left side. (CDC)

After birth, as pulmonary vascular resistance decreases and the ductus begins to close, the inadequate left‐side flow becomes impossible to sustain, leading to hypoxia, shock, and ultimately death unless interventions are done. (PubMed)

Embryology & Pathogenesis

The exact embryologic cause of HLHS is not fully determined. Some theories suggest that inadequate blood flow through the left‐heart structures during fetal development (due to e.g., aortic stenosis) leads to undergrowth of the ventricle and arteries (“flow‐related hypoplasia”). Others emphasise genetic and environmental factors. (BioMed Central)

Genetic associations have been identified (e.g., mutations in genes such as GJA1, NKX2-5, HAND1) though they account for only a subset of cases. (Wikipedia)

~Causes & Risk Factors

Known Associations

-

Genetic changes: While most cases are sporadic, some are linked to chromosomal anomalies (e.g., Turner syndrome, trisomy 13/18) or gene mutations. (MedlinePlus)

-

Other congenital defects: Around 10 % of HLHS cases have additional major birth defects. (Mount Sinai Health System)

-

There are likely environmental or maternal factors, albeit evidence is limited. The exact “cause” in most cases remains unknown. (Mayo Clinic)

Risk Factors & Recurrence

-

Having one baby with HLHS modestly increases the risk of another baby with a congenital heart defect, but the recurrence risk for HLHS specifically is low (~0.5 %). (BioMed Central)

-

Male infants appear to be somewhat more commonly affected. (BioMed Central)

~Clinical Presentation

Timing of Symptoms

Often, infants with HLHS appear fairly stable at birth because the ductus arteriosus and foramen ovale are still patent, enabling compensatory blood flow. However, within a few hours to days, as these fetal shunts begin to close and pulmonary resistance drops, the infant begins to deteriorate. (Cleveland Clinic)

Typical Signs & Symptoms

Signs may include:

-

Cyanosis (bluish‐gray coloration of skin, lips, nails) due to reduced oxygen delivery. (Mayo Clinic)

-

Rapid or difficult breathing, respiratory distress. (Mayo Clinic)

-

Poor feeding, difficulty in taking feeds, tiredness. (WebMD)

-

Weak or absent pulse in extremities; cool hands and feet due to low perfusion. (CDC)

-

Lethargy, low activity, signs of shock (cool clammy skin, rapid/weak pulse) if untreated. (MedlinePlus)

-

Sometimes hepatomegaly (enlarged liver) due to congestive failure. (PubMed)

Physical Examination & Early Clues

-

A loud single second heart sound (because of aortic atresia) may be present. (BioMed Central)

-

Murmurs may be subtle or absent; the key is recognition of rapid deterioration in the neonatal period. (PubMed)

-

When the PDA begins to close, systemic perfusion fails leading to acidosis, shock. (BioMed Central)

~Diagnosis

Prenatal (Fetal) Diagnosis

With modern fetal echocardiography and ultrasound, HLHS can sometimes be detected in utero, often in the second trimester. Features include: a small left ventricle, narrowing of the ascending aorta, etc. (UMMS)

Early prenatal diagnosis can be beneficial for planning delivery at a centre equipped for neonatal cardiac surgery.

Post-birth Diagnosis

-

Echocardiogram (ultrasound of the heart) is the key diagnostic tool — it delineates the anatomy of the left heart, valves, and flow. (Cleveland Clinic)

-

Pulse oximetry, blood gas analysis, ECG, chest X-ray may all be adjunctive.

-

Detection of low oxygen saturation, signs of systemic hypoperfusion in a newborn should prompt echocardiography.

Differential Diagnosis

Other congenital heart defects with cyanosis or left‐side obstruction must be considered (e.g., critical aortic stenosis, coarctation of the aorta). The hallmark of HLHS is the near‐absent or non‐functional left ventricle plus severely hypoplastic ascending aorta and aortic arch.

~Management & Treatment

HLHS is not curable in the sense of restoring a “normal two‐ventricle heart” in all cases, but management aims to allow survival and improve quality of life via a series of surgical interventions or transplantation. (CDC)

Immediate Newborn Management

-

Prostaglandin E1 infusion: To maintain the ductus arteriosus open (PDA) so that blood can flow from the right side to the systemic circulation. Without this, the infant may collapse. (PubMed)

-

Monitoring in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) with paediatric cardiology and cardiac surgery teams.

-

Support of breathing, circulation, control of acidosis, etc.

Surgical Treatment: The Staged Approach

Most centres adopt a three‐stage surgical reconstruction concept (sometimes with modifications). The goal is to re‐arrange the circulation so that the single (right) ventricle supports the systemic circulation and venous return from the body is diverted to the lungs in a controlled low‐pressure fashion (“Fontan physiology”).

-

Stage 1: Norwood procedure (or variant such as the Sano modification)

-

Done in the first few days to weeks of life.

-

The main pulmonary artery may be reconstructed to form a new aorta; the aortic arch is reconstructed; a shunt or conduit is placed to supply pulmonary blood flow. (aubmc.org.lb)

-

The result: the right ventricle pumps to the body, and a controlled shunt supplies the lungs.

-

-

Stage 2: Glenn (or Hemi‐Fontan) procedure

-

At around 3–6 months of age (varies by institution).

-

The superior vena cava is connected to the pulmonary arteries. This reduces volume load on the ventricle and improves efficiency.

-

-

Stage 3: Fontan procedure

-

At around 1.5–4 years of age (again variable).

-

The inferior vena cava flow is redirected into the pulmonary arteries (via conduit) so that venous blood returns passively to the lungs without passing through a ventricle. The single ventricle then exclusively pumps oxygenated blood to the body.

-

After this, the heart circulation is called “Fontan physiology”.

-

Transplantation

In some cases — e.g., when the anatomy is extremely complex, or the ventricle or other structures fail — heart transplantation may be considered. However, donor hearts for infants are scarce, and transplantation has lifelong implications (immunosuppression, risk of rejection). (CDC)

Hybrid Procedures & Innovations

Some centres use hybrid approaches (combining surgical and interventional catheter techniques) as alternative first‐stage strategies, especially when birth weight is low or the infant’s condition is unstable. Research is ongoing into stem‐cell therapy, improved imaging and computational modelling for single‐ventricle physiology. (arXiv)

~Outcomes & Prognosis

Historically

Before the development of the Norwood and subsequent staged surgeries (i.e., pre‐1980s), the survival of infants with HLHS was extremely poor — most died within days or weeks. (PubMed)

Modern Outcomes

Thanks to advances in surgical care, intensive care, and long‐term management, survival rates have improved dramatically: five‐year survival rates (for selected centres/patients) now approach ~70-80 % or more in favourable cases. (Wikipedia)

However, “survival to adulthood” remains challenging, and data on adults with HLHS are limited since the first cohorts only began reaching adulthood in recent decades.

Key Factors That Influence Prognosis

-

Birth weight (low birth weight worse)

-

Presence of non‐cardiac anomalies or genetic syndromes

-

Complexity of left‐side hypoplasia and how many structures are involved

-

Whether an atrial septal defect is restrictive (causing left atrial hypertension)

-

Centre volume: institutions performing higher numbers of HLHS repairs tend to have better outcomes. (Wikipedia)

Long‐Term Issues

Even after successful staging, children and adults with HLHS face multiple challenges:

-

Reduced exercise capacity; fatigue with exertion. (Mayo Clinic)

-

Arrhythmias (irregular heart rhythms) and risk of heart failure. (Mayo Clinic)

-

Liver congestion or dysfunction (in Fontan circulation), plastic bronchitis, protein‐losing enteropathy in some cases.

-

Neurodevelopmental issues: children with single‐ventricle physiology (including HLHS) are at higher risk of developmental delays, cognitive, language or executive‐function deficits. (Wikipedia)

-

Need for lifelong follow‐up with congenital cardiology, sometimes re‐intervention (catheter or surgical) and possible eventual need for transplantation.

~Living with HLHS & Follow-Up Care

Lifelong Monitoring

Children and adults with HLHS need multidisciplinary follow‐up: congenital cardiologists, heart failure specialists, electrophysiologists, imaging experts, sometimes transplant teams. Routine evaluations include echocardiography, MRI/CT, exercise testing, monitoring of liver/renal function.

Lifestyle Considerations

-

Physical activity: Many children can engage in moderate activity, but may have limitations compared with peers; tailored exercise plans help.

-

Nutrition, growth monitoring: Babies may have difficulty feeding early; long‐term growth and development need support.

-

Psychosocial support: Dealing with chronic illness, hospitalizations, and potential complications takes a toll; families and patients benefit from psychological and social support.

-

Pregnancy and adult life: As more children with HLHS reach adolescent/adult age, issues around pregnancy (for women), employment, insurance and transition to adult congenital heart disease care become relevant.

Family Planning & Genetic Counselling

Although recurrence risk is low, families should be offered genetic counselling given associations with certain syndromes and the possibility of subtle genetic predispositions. (rarediseases.info.nih.gov)

~Prevention & Screening

There is currently no known way to prevent HLHS in most cases. As per the Mayo Clinic, the cause is generally unknown. (Mayo Clinic)

However, early detection is critical. Screening of newborns via pulse oximetry (in many countries) may help detect critical congenital heart disease – though HLHS needs echocardiography for diagnosis. Fetal ultrasound, if done in high‐risk pregnancies or when abnormalities are suspected, can detect HLHS prenatally and allow delivery planning at specialised centres.

~Special Considerations in Resource-Limited Settings (such as India)

In India and other lower‐middle‐income countries, the challenges are magnified: availability of specialised paediatric cardiac surgery centres, neonatal intensive care, affordability, access to tertiary care, and long‐term follow‐up may be limited. Early referral, focusing on high‐risk pregnancies, and establishing regional congenital heart disease programmes are important. The burden of congenital heart disease is huge in India and HLHS, while rare, presents a large challenge.

~Research & Future Directions

Research in HLHS is actively progressing:

-

Stem‐cell and regenerative therapies: Some early trials are exploring cardiac progenitor cells and mesenchymal stem cells to improve single‐ventricle function. (Wikipedia)

-

Computational modelling and imaging: Advanced MRI, computational fluid dynamics are being used to understand the unique haemodynamics of single‐ventricle circulation in HLHS patients and to optimise surgical/interventional strategies. (arXiv)

-

Machine learning in fetal imaging: Some studies (e.g., using deep‐learning) aim to improve accuracy of prenatal detection of HLHS. (arXiv)

-

Long‐term outcomes into adulthood: As more HLHS patients reach adult age, studies are focusing on quality of life, organ damage (liver/Kidney), arrhythmia management, and transplantation timing.

-

Hybrid surgical/interventional techniques and earlier neonatal interventions are also under investigation.

~Case Illustration & Considerations

Imagine a baby born at full‐term with initially unremarkable appearance, but 24 hours later becomes pale, has rapid breathing, a weak pulse and cool extremities. Pulse oximetry shows low oxygen saturation. An echocardiogram reveals a tiny left ventricle, aortic atresia, and patent ductus arteriosus. Prostaglandin E1 is started; the baby is transferred immediately to a paediatric cardiology/ICU centre. Within the first week the baby undergoes the Norwood procedure. Over the next months and years the child has staged Glenn then Fontan procedures, followed by periodic follow-up. The child will require lifelong care, monitoring for complications (arrhythmia, heart failure, liver issues), and psychosocial support as they grow.

This simplified scenario highlights the urgency and complexity of HLHS care.

~Ethical & Psychosocial Dimensions

The diagnosis of HLHS often presents serious ethical questions: given the severity, many parents face difficult decisions regarding surgery vs comfort care. Informed counselling is crucial.

Psychosocially, families must deal with repeated hospitalisations, interventions, uncertain prognoses, and the possibility of long-term disability or reduced exercise tolerance. Support groups, parent networks and mental health resources are vital.

As survivors enter adult life, issues around employment, insurance, transition of care, reproductive counselling (for female patients), and independent living become salient.

~Summary & Key Take-Home Points

-

HLHS is a major congenital heart defect in which the left‐side cardiac structures are severely underdeveloped, and the right ventricle becomes the systemic pump.

-

It is rare, but carries high urgency: untreated, it is usually fatal in early life.

-

Early recognition, maintenance of ductus via prostaglandin, urgent surgical staging (Norwood → Glenn → Fontan) or transplantation are the mainstays of treatment.

-

Survival has improved significantly over recent decades, but survivors remain at risk of lifelong complications and need lifelong follow‐up.

-

There is no known prevention, so early diagnosis (prenatal or neonatal) is important for referral to specialist centres.

-

Research is ongoing into better diagnostic tools, surgical/interventional strategies, regenerative therapies and long‐term adult outcomes.

-

In resource‐limited settings, challenges of access, cost, follow‐up and long‐term care are amplified.

-

Families and patients need multidisciplinary support (medical, psychological, social) to navigate the journey.

~Conclusion

Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome represents one of the most challenging congenital heart defects in paediatric cardiology. The evolution of surgical and medical care has transformed it from an almost uniformly fatal condition to one in which many children survive, grow, and transition into adulthood. However, “survival” is only the beginning—ensuring good quality of life, preventing complications, and supporting lifelong health remain major tasks. Advances in imaging, genetics, surgery, and supportive care will continue to improve outcomes, but the complexity of HLHS demands coordinated care, early diagnosis and a holistic approach to patient and family wellbeing.

No comments:

Post a Comment